Why Implementing Single Responsibility Principle is Hard

Software Responsibility is a language problem before it is a design problem. From "House Red" sauce mishaps to half-billion-dollar trading errors, discover how "Language Debt" collapses system navigation and how the "And" Test can save your codebase.

The "House Red" Sauce

In every busy restaurant kitchen, there is a House Red—the reliable, all-purpose tomato base used for everything from pastas to starters. For years, the staff has a shared, unspoken understanding: the House Red is dairy-free. Because of this reliability, the staff develops a habit of reaching for it every time a customer requests a vegan sauce.

Then, the chef makes a "tiny" upgrade. To make the lasagna richer, they stir heavy cream into the House Red. It tastes better and saves time, but crucially, nobody updates the label on the prep list. The next night, a customer orders dairy-free penne. The server, relying on years of habit, rings it up with House Red, unaware that the ingredients have changed.

The result is a medical emergency and a shattered reputation, only because the kitchen’s language stopped being reliable. This is the birth of Language Debt: the moment a label becomes a lie because its meaning changed while its name stayed the same. This is the hidden architecture of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

Architecture as a Navigation System

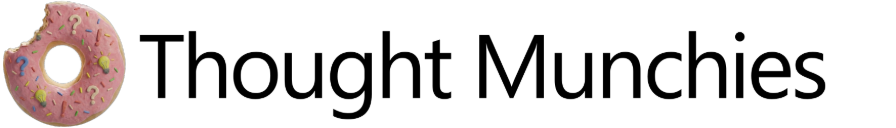

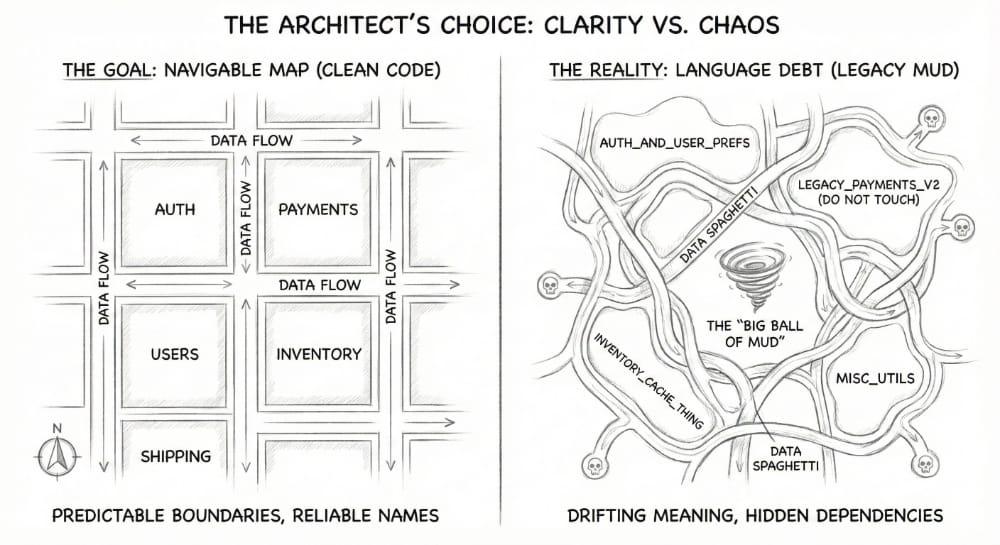

In software engineering, we often treat "responsibility" like a vibe, a general sense of what a class is about. But as a system grows, architecture stops being about principles and starts being about navigation. Once a codebase is large enough that no one person can hold the full map in their head, it becomes a library that never stops expanding.

In this library, the modules are aisles, the services are floors, and the boundaries are the shelf labels that tell you where a certain kind of code is supposed to live. When something breaks, engineers rarely debug by reading everything end-to-end. They debug the way you find a book in a massive library:

- Start with a symptom. An engineer forms a rough category. "This feels like auth" or "this feels like persistence", to narrow the search from the whole library to a few aisles.

- Use architecture as the index. Names and boundaries act as the first filter to find the specific package or component that should own that behavior.

- Confirm fast with shallow reading. You skim interfaces and entry points to ask, "Am I in the right section?" before paying the high cost of deep understanding.

- Trace dependencies to estimate blast radius. You ask what depends on this and what could break, separating a safe fix from a surprise incident.

- Go deep. Deep reading only happens once the map has successfully led you to the right neighborhood.

Language Debt is what happens when those library labels drift. The signs stay the same, but they no longer match what is inside. When the index becomes a liar, navigation collapses. You start in the wrong place, misjudge the blast radius, and eventually, the codebase becomes a forest you can only traverse with flashlights.

The $440 Million Worth House Red

If the "House Red" story is a kitchen mishap, the Knight Capital disaster is the same failure at an industrial scale. On August 1, 2012, Knight Capital lost roughly $440 million in just 45 minutes.

The mechanism was painfully simple: a coordination switch kept its name while its meaning changed. To participate in a new NYSE program, engineers repurposed an old, dormant utility called "Power Peg". Years earlier, Power Peg was a test utility used to move stock prices up or down to observe system behavior; it was never meant to trade real money.

When the new code was deployed, they failed to update the old flag used to activate it. On one out of eight servers, the update was missed, and the old code remained. When the command hit that server, it didn't see "New NYSE Program", instead it saw its original responsibility: Execute Power Peg.

The system began buying and selling massive volumes as if the live market were a test harness. In the scramble to stop it, the team reverted the deploy, which only made the failure worse by triggering the old Power Peg code on all eight servers. The label kept its shape while its meaning changed, and that mismatch became a half-billion-dollar mistake.

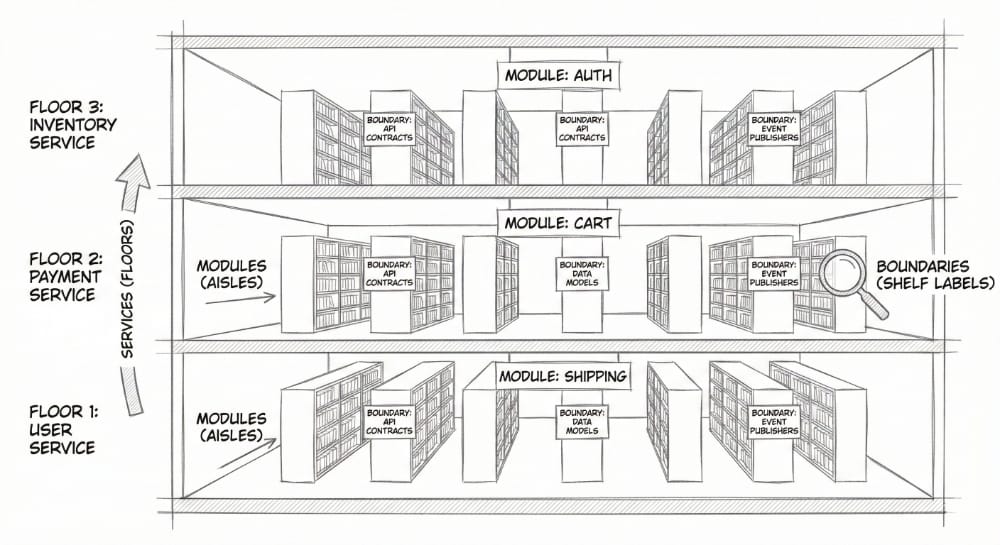

Anatomy Of The Drift: The ExpenseStore

Most architectural messes begin with a change that looks helpful and feels local. Consider a class called ExpenseStore. In the beginning, it has one job: read and write expenses to persistence.

class ExpenseStore:

def save(user, expense):

# Write to persistence

def list(user):

# Read from persistence

At this stage, the name correctly compresses reality. If you hear ExpenseStore, you expect persistence semantics. But then, a "convenient" improvement arrives: Caching. You add a cache to speed up reads. It seems like an implementation detail, but it fundamentally changes what callers observe.

The moment you introduce a TTL (Time-to-Live) or invalidation rules, you have introduced staleness semantics. Now, list(user) doesn't just return data; it decides which version of reality counts as "the user's expenses."

class ExpenseStore:

def save(user, expense):

# Write logic

def list(user):

# Return Data from cache or persistent storage

Years later, a ticket arrives: "Users are seeing old expenses for a few minutes after an update." The investigation rarely starts in ExpenseStore because the name doesn't advertise that it contains caching logic. Engineers waste hours looking at the UI or the database until they "rediscover" that "store" was also silently choosing staleness rules.

The 4-Step "Drift" Sequence

This failure follows a predictable pattern:

- A clear contract exists: A name, flag, or class has one shared, predictable meaning.

- Convenience expansion: A new feature "piggybacks" on the old thing because it is already there.

- Expansion is not made explicit: The name stays the same, but the responsibility changes. The system now contains two truths: what it sounds like vs. what it actually does.

- Context splits: Different teams, services, or environments interpret the identifier differently, leading to a collision.

Once you see architecture as navigation, the fix stops being abstract. You are not trying to make the codebase “clean” for its own sake. You are trying to keep the system readable so that the next person or future you, can identify where things live and what they do, without having to rediscover meaning through runtime experiments.

The "And" Diagnostic

To identify drift before it becomes debt, use a simple linguistic test: If you have to explain a component in one sentence and you need the word "and," the boundary is already cracking.

- Honest: "It stores expenses."

- Drifting: "It stores expenses and enforces freshness policy."

That "and" signals that the contract has expanded beyond what the name can compress. This increases the cognitive load of every future code review because the reader must reconstruct the hidden contract before they can judge the change.

What To Do When You See Drift

Senior developers must act as the "immune system" for the codebase. When you notice drift in a Pull Request, you have two options:

- Extract the responsibility: Keep

ExpenseStorea store. Move caching policy into a dedicated layer. Give each boundary a name that matches what it actually promises. - Promote the responsibility: If the concerns truly belong together, rename the contract so the system speaks the truth.

CachedExpenseStoremay not seem pretty, but it is honest.

The Human Limitation: Culture And Structure

The Single Responsibility Principle is not a self-executing law; it is enforced socially. It only works when a team has the habit of naming boundaries, challenging scope creep, and rewarding cleanup.

In cultures where speed is the only visible currency, responsibility creep becomes the path of least resistance. Furthermore, organizational structure often dictates code: when a feature spans multiple teams, systems naturally gravitate toward "just adding it here" to reduce short-term coordination overhead. SRP becomes hardest exactly where the software is most valuable: at the seams between teams and domains.

Conclusion: One Small Habit

SRP is the discipline of keeping a boundary’s contract single-meaning, so the name stays a reliable predictor of behavior and blast radius. When you touch a boundary, do not let new meaning sneak in under an old label. Either isolate the new responsibility, or rename the contract so the team keeps speaking the same language.

That is what responsibility looks like when it stops being a vibe and becomes a contract.

BONUS: 4 Concrete Questions To Qualify Your Component

Share these questions with your team to help identify responsibility drift during design or review:

- The "And" Test: Can you describe the component's purpose in one sentence without using the word "and"?

- The Predictability Test: If a teammate only saw the name of this component, could they accurately predict what will break if it changes?

- The Coordination Test: Is this component using a shared identifier (flag or config key) that originated in a different domain?

- The Change Test: How many distinct policies live inside this boundary (storage, meaning, freshness, rollout), and which of those should be named explicitly?