The Street Sweeper Trap: Why Your Solutions Are Just Creating More Work

A city has pristine streets, but 5000 sweepers scrub them daily at a huge cost. This is the "Street Sweeper Trap." We often fall into the trap of solving symptoms with effort instead of architecture. Stop being the janitor of your team; start being its architect. Learn the 4-step framework.

The Illusion of Cleanliness 🧹

You enter a city where the sidewalks are pristine, but every morning at 9:00 AM, a fleet of five thousand street sweepers descends upon the streets. They are loud, they block traffic, and they cost the city half its annual budget.

If you ask the mayor, he will tell you the city is a model of cleanliness. He points to the absence of litter as proof of success. But if you look closely, you realize the sweepers are only there because the trash bins are three blocks apart and the lids are too heavy to lift. The city isn't actually clean; it is just being constantly, exhaustively scrubbed.

Two Approaches to Simplicity

In product development, business leadership, and even national policy, we often fall into the "Street Sweeper Trap." We see a mess, a dipping metric, a frustrated user, a complaining team, and our default move is to throw labor and "obvious" fixes at the problem.

This article is about the choice between two distinct paths to simplicity:

- Patch Simplicity: This is the "first thing that comes to mind." It is the street sweeper approach. Labor-intensive, reactionary, and focused on masking symptoms to provide localized relief.

- Structural Simplicity: This is the "minimum necessary thing considering all aspects." It involves a discovery phase to identify the underlying driver and ship a structural change that prevents the mess from occurring in the first place.

Fixing the symptom is ultimately costlier than identifying and fixing the root cause. While patches give you bounded solutions, structural fixes provide exponential improvements.

The Symptom Fix That Feels Like Progress

We want to feel productive. There is almost a dopamine hit that comes from "doing something" during a crisis. And symptoms are LOUD; they create an urgency that makes you feel like you’re falling behind.

Most of us solve problems like that mayor. We see a mess and we throw labor at it. A team feels slow, so you add a new layer of process. A metric dips, so you cut a step from the user journey. We invest in "Cleanup Months," or "Compliance Syncs." We mistake the removal of the symptom for the cure of the disease.

The hidden cost isn't just the money spent on sweepers; it is the "sweeper fatigue" of the people doing the work. When you solve a problem with effort instead of architecture, the moment the effort stops, the mess returns. You spend your cycles fixing symptoms and hiding the actual fix underneath them, iterating on the same problem over and over while leaving the engine that generated the problem intact.

"Shorter" Is Not the Same as "Simpler"

In product design, the most common "street sweeper" move is removing friction without understanding the intent. "Reduce friction" is a seductive phrase because it sounds like common sense. If activation is flat and users drop off during onboarding, the obvious story is: there are too many steps.

So you cut. You streamline the UI and hide fields. Conversion bumps, and the sidewalk looks clean for a moment. But then, the metric flatlines again and churn follows.

The product became easier to enter but harder to succeed in. You removed effort, but you also removed the clarity, trust, or path to the first successful moment that the user actually required. The onboarding got shorter, but the experience did not get simpler, it just became more ambiguous.

Symptoms vs. Conditions: Moving the Bin

A symptom tells you where the system is complaining; it does not tell you where the system is broken.

The goal of problem-solving shouldn't be to get better at cleaning up messes. The goal should be to make the mess impossible to create. To do that, we have to stop looking at the trash on the ground and start looking at the path people walk. We need to move from Managing Symptoms to Designing Outcomes.

Think of it like a car's check-engine light. Putting tape over the light "fixes" the visual symptom of the alert, but the engine is still failing. Or consider a crack in a wall: you can patch the plaster (the symptom), but if the foundation is shifting (the condition), the crack will return. In the city metaphor, the trash is the dashboard; the distance between bins and the weight of the lids are the drivers.

Choosing Your Path: Maintenance Habit vs. Compounding Growth

A useful way to think about this is that there are two kinds of simplicity:

Patch Simplicity is what you get when you remove the most visible rough edge. It looks like:

- Fewer steps in a flow

- more documentation to explain a complex system

- "Just fix the tests" energy.

This isn't inherently bad during a fire, but its failure mode is dangerous: it increases the system’s maintenance load. You end up doing the same fix repeatedly because the underlying conditions never changed. You aren't building; you are maintaining a habit of repair.

Structural Simplicity is what you get when you change the conditions so the pattern stops. It focuses on:

- Better Defaults: Making the "right" path the easiest.

- Stronger Constraints: Narrowing the field to prevent errors.

- Aligned incentives: Rewarding the desired behavior.

Structural simplicity compounds because it reduces future maintenance work. It frees the team to focus on new challenges rather than litigating old ones.

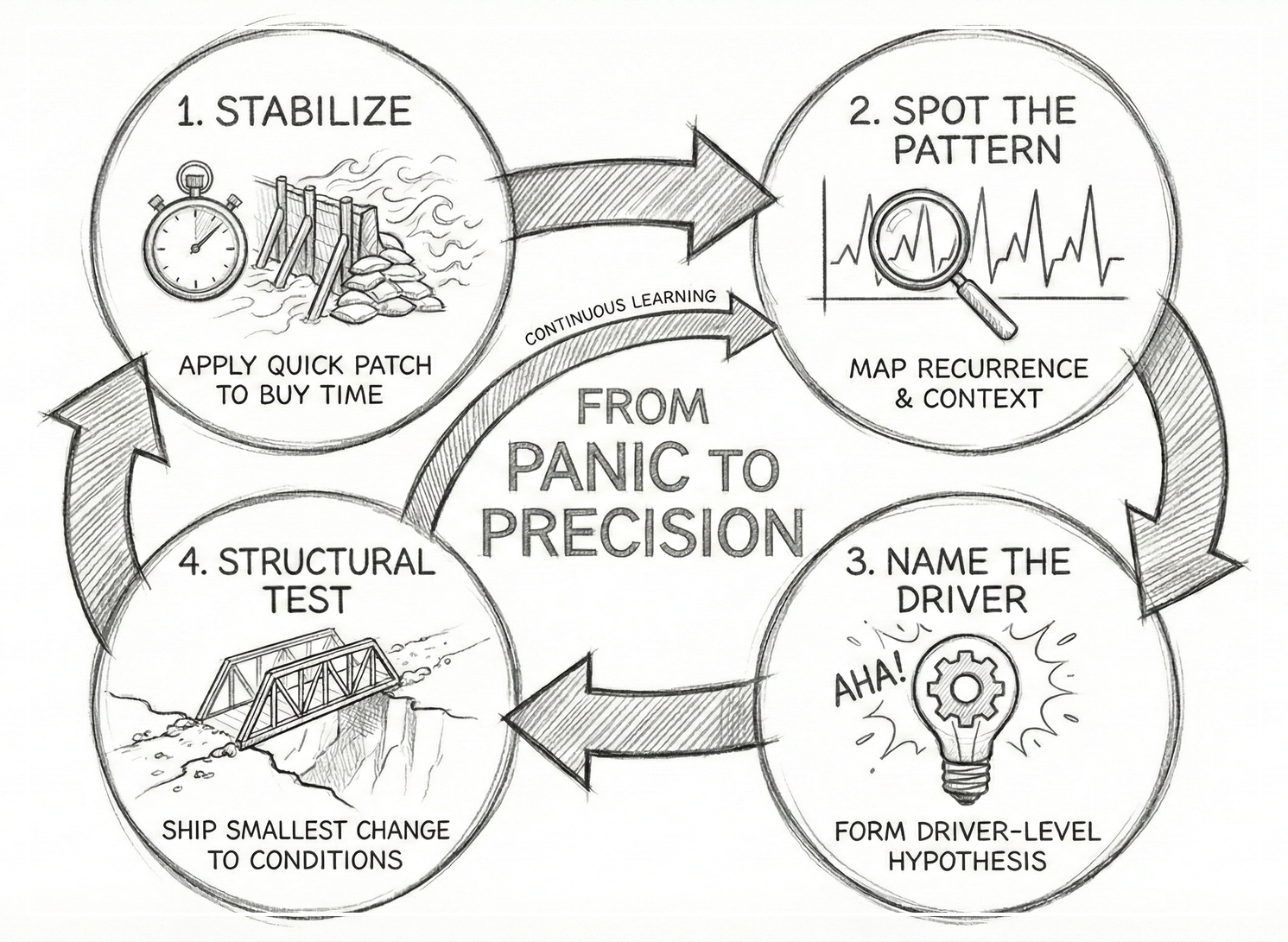

The Four-Step Loop: Turning Panic into Precision 🛠️

True systems thinkers use a specific sequence to move from chaos to a permanent state of "clean."

- Stabilize: You still need the street sweepers initially. If users are being harmed or if the team is bleeding time, apply a patch (the "quick patch") to buy time to think. Do not romanticize the chaos; stabilization creates the room for diagnosis.

- Spot the Pattern: Once the streets are clear, watch what repeats. Is the trash always near the bus stop? Does the onboarding friction only happen for a specific user segment? Mapping the recurrence across time and contexts reveals the system's "gravity."

- Name the Driver: This is the "Aha!" moment. You form a driver-level hypothesis. The driver isn't "lazy citizens"; the driver is that the bus stop has no bin. In product, drivers are often constraints, incentives, or low confidence.

- Deliver a Structural Test: Ship the smallest change that alters the system's environment to test your hypothesis. This is the Strategic MVP. If you install a bin and that corner stays clean for a week without a sweeper, you have found a structural solution.

Applying the Loop to Onboarding (Without Just Cutting Steps)

Consider a user, Alex, who encounters a project management tool. The first screen demands his Company Tax ID without explaining why or what he gets in return. His confidence flickers. He clicks through two more screens but finds no incremental value. Before he can "Invite his team," he closes the tab.

The "Street Sweeper" fix is to just delete the field. But the Structural Fix is different. Alex’s driver is low confidence. He is being asked for "high-cost" info before receiving "high-value" proof.

Applying the loop:

- Stabilize: Add a "Why do we need this?" tooltip to reduce immediate confusion.

- Spot the Pattern: Users linger on this screen for 30 seconds before dropping off.

- Name the Driver: Ambiguity and lack of trust. Alex is asked for high-cost data before receiving high-value proof.

- Structural Test: Progressive Disclosure. This technique hides complex features or requirements until they are needed. Move the Tax ID requirement to the final setup step. Allow Alex to explore and add tasks first. Now, when the system asks for the ID, he isn't providing it to a stranger; he’s providing it to a tool he’s already using.

When Patches Are Actually the Right Move

It would be a mistake to turn this into a moral story where patches are always wrong. A band-aid solution is a strategic tool when waiting for a structural fix costs more than the patch's "waste."

- To Stop the Bleeding: When a bug corrupts data, apply a hotfix immediately.

- To Manage Optics and Trust: If a "yellow leaf" distracts a stakeholder, a quick optical fix buys the political capital needed for slower, subterranean work of structural change.

- To Gather Intelligence: Ship a manual version of a feature to see if anyone uses it before building the automated engine.

A patch is a loan: it gives you time today at the expense of interest tomorrow.

The question is not whether you patch. The question is whether you stop there.

The Trap: Discovery Theater 🎭

In the halls of government and Big Tech, "finding the root cause" is frequently used as a synonym for "kicking the can down the road."

Take the teen mental health crisis. When social media companies are questioned about addictive algorithms, the response is often a call for "more research," arguing the issue is "multi-faceted.". While true, this is Discovery Theater. It shifts focus from the engine—specific design choices like infinite scroll—to broad societal drivers. Demanding a decade of academic consensus successfully stalls any structural test.

If the conversation about "drivers" doesn't produce a testable hypothesis and a small next move, it is just a delay tactic. The antidote is to timebox the discovery. State the driver as a hypothesis, set a deadline, and ship a structural test. Learn by doing, not by hiding behind infinite complexity.

A Quick Note on "Faster Horses" (Solution-Language vs. Job-to-be-Done)

People describe their needs in the language of the tools they already know.

Take the 50-year mortgage being discussed in the US as an "affordability fix." On the surface, it addresses the "loud" symptom of high monthly payments. But the driver isn't the loan length; it's a lack of housing supply. Stretching the loan is watering a plant with root rot. It might hide the symptom, but by making it "easier" to borrow more for fixed supply, it may drive prices higher.

Your job is to translate solution-language into the underlying "job," then test a structural change, like increasing supply, that reduces the constraint.

Audit Your Solution: The Three-Question Litmus Test

Use these questions to audit your solutions before shipping:

- Does the fix depend on ongoing vigilance? If it requires someone to "remember" a manual check, it’s a patch. A structural fix changes the environment so they can’t forget.

- Will we be doing this again next month? If the logic is localized to an event rather than a pattern, the symptom will return.

- Does it reduce future work or create a new habit? Every patch creates a "maintenance habit." Structural simplicity should feel like a weight being lifted.

Conclusion: From Reaction to Design

A truly healthy system is quiet. It doesn’t need a fleet of sweepers or a megaphone to keep things in order.

When a team is forced to be "street sweepers" for a broken system, morale tanks. They know the trash will be back tomorrow. However, when you involve a team in "Naming the Driver," you shift them from manual labor to systems engineering. They stop being the janitors of the product and start being its architects.

If you find yourself constantly cleaning up the same mess, stop looking at the broom in your hand. Look at the map of the city. That is how you stop reacting and start designing.